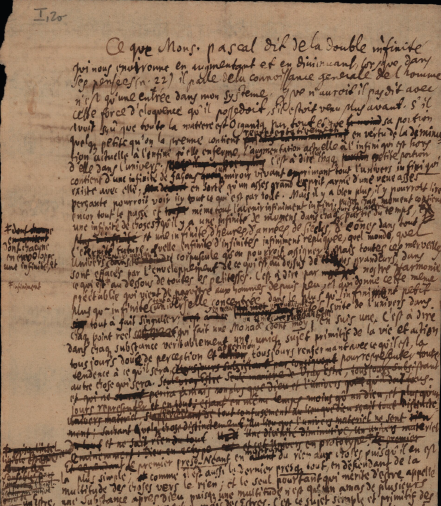

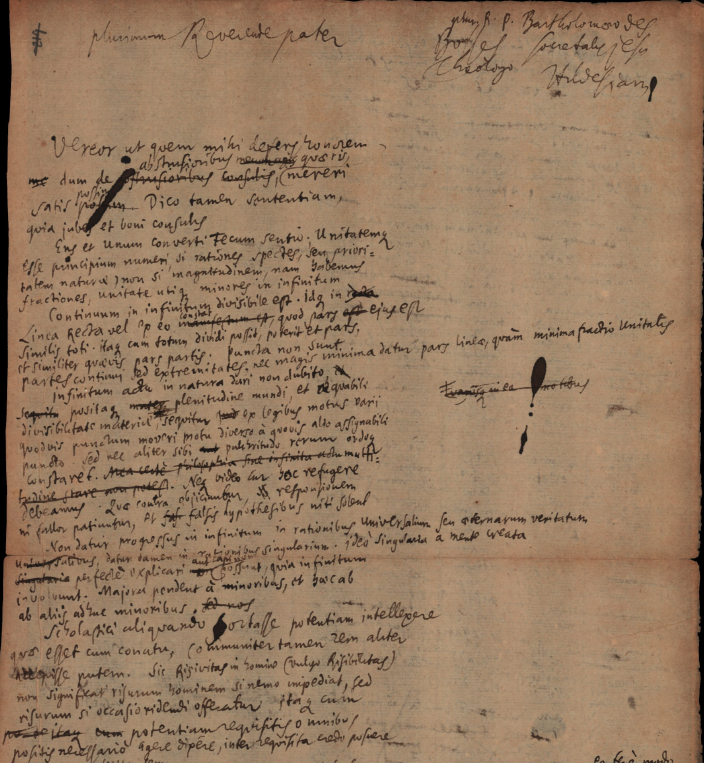

Barthélemy Des Bosses to Leibniz, Hildesheim, 2 March 1706

2 March 1706

Barthélemy Des Bosses to Leibniz, Hildesheim, 2 March 1706

Illustrissime Domine

P[ax] C[hristi]

Posterioribus litteris tuis mihi longe gratissimis distuli respondere, quod te brevi profecturum putarem; nunc cum ex Cl. Behrens intelligam iter tuum non tam cito processurum, audeo novas circa responsum tuum dubitationes proponere, quibus, si ejusmodi videbuntur quae alios quoque remorari queant, tu, cum erit commodum tuum, respondebis. Nolo enim abuti humanitate tua, aut pretiosissimum tempus tuum mea causa inutilibus officiis impendi. Interim dubiis hisce meis, sive ex praejudiciis nascantur, sive ex non satis percepta mente tua, eluctari non possum, cum tamen, ut sapienter mones, de multis non bene decernatur nisi omnia sint in conspectu.

Ac imprimis, si ens et unum convertuntur, nihil igitur simpliciter et actu extat a parte rei nisi quod est unum actu simpliciter; sed fractio unitatis sive unius actu simpliciter, non est unum actu simpliciter, alioqui unum ex Materia et Entelechia constans, cujus fractionem accipimus, esset aggregatum unitatum, adeoque non unum. Erunt igitur fractiones unitatis cujusque simplicis entia tantum mathematica quae abstractionem mentis consequuntur.

Rursus: quaelibet pars materiae existit, ergo quaelibet pars materiae est una vel multae; si multae, pars partis est una, nam ubi non est unum, neque sunt multa. Porro hoc quod unum est, non est multa. Ergo materia quatenus substat uni entelechiae, non est multa actu.

2°Aveo scire an infinitum actu in magnitudine perinde atque in multitudine admittere necesse sit in natura? Ptolemaeus quidem primum respuit, asserto secundo: sed an ejus sententiam ac solutiones probas? Si non; suggere mihi, obsecro, autorem quempiam, quem in propugnando infinito ducem sequi tuto possim, aut saltem clavem difficultatis verbo indica, nam falsas hypotheses, quibus infiniti adversarios niti ais, non deprehendo, nec quenquam vidi qui mihi satisfaciat.

Monebas alias in Trivultiano Diario, ubi de calculo differentiali sermo erat, necesse non esse ut rigide sumatur infinitum, et in Specimine tuo Dynamico postquam de infinitis impetus gradibus locutus es, subdis: quanquam non ideo velim haec entia mathematica reapse sic reperiri in natura, sed tantum ad accuratas aestimationes abstractione animi faciendas prodesse. Ex quo duplici loco ansam ceperam opinandi infinitum quod adstruis intra syncategorematici fines contineri posse, quid enim vetat,

quominus id quod de impetus gradibus dicitur, ad substantiarum multitudinem transferamus? An plenitudinem mundi et aequabilem materiae divisibilitatem legesque motus varii explicari pariter non posse censes citra infinitum, actu stricte sumptum?

3° Cum ais nullam partem substantiae corporeae, imo nec partem partis esse quae monadas non contineat, vel vis eandem praecise materiam pluribus simul Entelechiis informari, vel aliam materiae partem alii Entelechiae; singulas singulis, nullamque pluribus subesse? Non primum opinor, alioquin dici posset quamlibet materiae partem omnes formarum saltem inanimatarum species continere, sicque materiae homogeneitas statueretur, et varietas tolleretur, ergo secundum asserendum. At Entelechiae

(utpote infinitae), cum in materia sint, singulae singulas materiae particulas infinite parvas sortientur, quae tamen ipsae divisibiles rursus erunt. Dividatur ergo earum aliqua. Sane cum Entelechiae istae nec destrui possint nec dividi sed nec nova possit produci a natura, alterutrum consequetur, ut ea, cujus materia separata est, Entelechia unam ex partibus a se invicem separatis sequente, remaneat altera materiae pars sine Entelechia, vel ut pars illa deserta accrescat aliis monadibus vicinis, sicque mutetur unitatum substantialium essentia.

4° Animantia bruta non intereunt, alioqui animae eorum, quae non intereunt remanereat in natura inutiles. Quid ergo fiet, si, ut fieri potest, partes machinae organicae, cui animae illae affixae sunt separentur ab invicem?

5° In dissertatione contra Cl. Sturmium, negas dari potentiam quae non sit active motrix. Quid igitur fiet materia, quae utique potentia passiva est?

Denique, dum ais causas secundas acturas, si nullum adsit impedimentum, vel intelligis impedimentum negativum vel positivum: si ais acturas si nullum adsit impedimentum negativum; jam requiris occasionem sive conditionem positivam ad hoc ut homo rideat. Nam impedimentum negativum tollitur tantum per aliquid positivum. Si dicis acturas si nullum adsit impedimentum positivum: Ponamus igitur nihil extare in rerum natura praeter unicam substantiam corpoream constantem materia et Entelechia unica, hoc casu substantia ista infinitas actiones ponet simul, non enim habebit impedimentum positivum. Nec erit ratio quare pauciores ponat, aut quare unam potius ponat, quam aliam.

Praeterea sola anima in homine libera est; igitur machina illius organica producit motum sui liberum aut spontaneum occasione motus spiritualis ab anima producti, quae tamen occasio non sollicitat ut causa sed ut conditio.

Comitiorum nostrorum eventum utique intellexeris. Primo scrutinio, obvenerunt P. Michaeli Angelo Tamburino 40 suffragia, P. Guilielmo Daubentonio 25, P. Joanni Vincentio Imperiali 8, P. Joanni Baptistae Ptolemaeo 4, P. Angelo Alamanno 3, et denique P. Curtio Sestio 1. Cum nemo suffragiorum dimidiam partem obtinuisset, itum est ad scrutinium alterum, quo demum P. Tamburinus suffragia adeptus est 62, P. Daubentonius 20, P. Imperialis 1. Rumor est de Ptolemaeo creando Cardinale.

Precor illustrissimae Dominationi tuae iter felicissimum utique sanus ac incolumis brevi ad nos revertaris. Dabam Hildesii 2 Martii 1706.

Illustrissimae Dominationis tuae

Servus Humillimus et obedientissimus

Bartholomaeus Des Bosses SJ

TRANSLATION

Barthélemy Des Bosses to Leibniz, Hildesheim, 2 March 1706

[Hildesheim, 2 March 1706]

Most Distinguished Sir,

The Peace of Christ,

I have long put off replying to your last, most welcome letter, for I thought that you would be departing shortly. Now, since I understand from the excellent Behrens that your journey will not begin very soon, I venture to raise some new questions about your response. If they seem to be of the sort that might also delay others, you will reply to them at your convenience, for I do not want to abuse your kindness or have your most precious time expended on my account with useless obligations. In any case,

here are my doubts; whether they arise from prejudices or from not having fully grasped your views, I cannot determine, since in any case, as you wisely point out, many matters are not properly decided unless everything is before the eyes.

To begin, if being and one are convertible, then nothing will exist in reality simply and actually except what is actually and simply one. But a fraction of unity, or of what is actually and simply one, is not actually and simply one, for otherwise one thing composed of matter and entelechy, whose fraction we are supposing, would be an aggregate of unities, and so not one. Therefore, fractions of unity and of any simple thing will be only mathematical beings that result from a mental abstraction.

Again: any part of matter exists, therefore any part of matter is one or many; if many, a part of the part is one, for where there is not one, there are not many. Moreover, that which is one is not many. Therefore, matter, insofar as it remains with one entelechy, is not actually many.

Second, I am eager to know whether it is necessary to admit in nature an actual infinity in magnitude, and consequently also in multitude. Tolomei, of course, rejected the first, while defending the second. But do you approve of his view and his solutions? If not, I beg you to refer me to any authority whose lead I could safely follow in defending the infinite, or at least point out briefly the key to the problem, for I do not perceive the false hypotheses on which, according to you, adversaries of the infinite depend, nor have I found anyone who satisfies me.

You indicated on another occasion in the Mémoires de Trévoux, when discussing the differential calculus, that it is not necessary that the infinite be taken rigorously; and in your “Specimen of Dynamics,” after having spoken of infinite degrees of impetus, you say: “although I would not claim on that account that these mathematical entities as such are actually found in nature but only that they are useful for making accurate estimates by means of a mental abstraction.” From what you say in these two places, I would have conjectured that the infinite that you add can be confined to the syncategorematic; for what prevents us from transferring what you say about degrees of impetus to a multitude of substances? Or do you believe that the plenitude of the world, the uniform divisibility of matter, and the laws of varying motion cannot all be explained unless an actual infinite, strictly speaking, is assumed?

Third, when you say that there is no part of a corporeal substance, nor indeed a part of a part, that does not contain monads, do you mean that precisely the same matter is informed by many entelechies at the same time, or that different parts of matter are informed by different entelechies, one by one, with no part being subjected to many entelechies? I do not imagine it is the first, for otherwise it could be said that any part of matter contains every species of inanimate form at least, and in this way the homogeneity of matter would be established and variety destroyed. Therefore, the second must be asserted. But, since they are in matter, the entelechies (seeing that they are infinite) will receive, one by one, infinitely small parts of matter, which nonetheless will themselves be divisible in turn. Therefore, any of these parts may be divided. Of course, since the entelechies themselves cannot be destroyed or divided, nor can a new one be produced naturally, one of two things will follow: in those whose matter is divided, either the entelechy stays with one of the separated parts, while the other part of matter remains without an entelechy; or the abandoned part is added to other nearby monads, and thus the essence of substantial unities may be changed.

Fourth, beasts do not perish, for otherwise their souls, which do not perish, would remain useless in nature. What then happens if, as could happen, the parts of an organic machine, to which those souls are attached, are

separated from one another?

Fifth, in your essay against the celebrated Sturm, you deny that there is a power that is not actively motive; what then becomes of matter, which is assuredly a passive power?

Finally, when you say that secondary causes will act if no impediment is present, you understand either a negative impediment or a positive one. If you say that they will act if no negative impediment is present, then you already require a positive occasion or condition for it to happen that a man laughs, for a negative impediment is removed only through something positive. If you say that they will act if no positive impediment is present, let us then suppose that nothing exists in the universe except a single corporeal substance composed of matter and a single entelechy; in this case that substance will presuppose infinite actions at the same time, for it will have no positive impediment, nor will there be any reason to suppose fewer actions, or to suppose one rather than another.

Furthermore, the soul alone is free in man; therefore, its organic machine produces its free or spontaneous motion on the occasion of a spiritual motion produced by the soul, but the occasion does not induce this as a cause but as a condition.

You will no doubt have heard the result of our election. On the first ballot, forty votes went to Father Michelangelo Tamburini, twenty-five to Father Guillaume Daubenton, eight to Father Giovanni Vincenzo Imperiale, four to Father Giovanni Baptista Tolomei, three to Father Angelo Alamanni, and finally one to Father Curzio Sesti. Since no one received a majority of the votes, it went to a second ballot, in which Father Tamburini at last got sixty-two votes, Father Daubenton twenty, and Father Imperiale

one. There is a rumor that Tolomei is to be made a cardinal.

I pray, most distinguished Sir, that you may enjoy a most happy journey and that you will return to us soon healthy and unharmed. From Hildesheim, 2 March 1706.

Your Excellency’s most humble and obedient servant,

Bartholomew Des Bosses, S.J.

⇐ BACK

-

Dr. Osvaldo Ottaviani

Translation