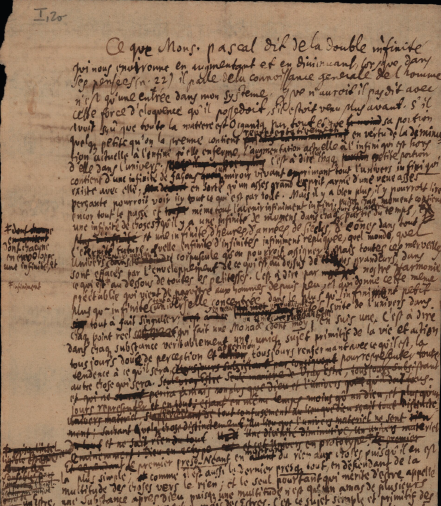

Leibniz to Des Bosses, Hannover 11-17 March 1706

11-17 March 1706

Leibniz to Des Bosses, Hannover 11-17 March 1706

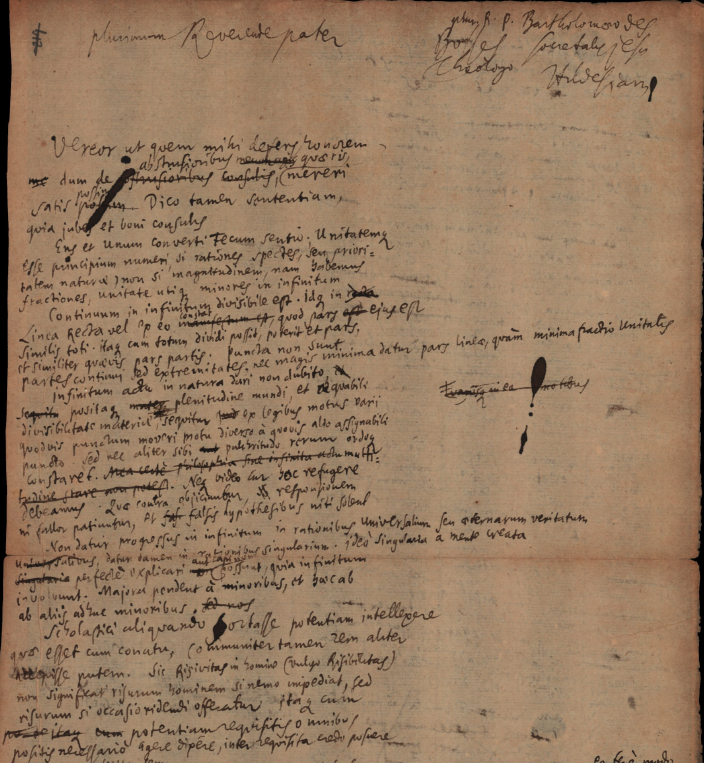

Plurimum Reverende Pater

Hoc incommodo tempore, valetudinis causa nonnihil distuli iter. Cum dubitationes Tuae res gravissimas et difficillimas attingant, aequi bonique consules, si praestem, non quae postulat rei dignitas, exigitque acumen Tuum, sed quae ferunt vires meae.

Ens et unum convertuntur, sed ut datur Ens per aggregationem, ita et unum. Etsi haec Entitas Unitasque sit semimentalis.

Numeri, Unitates, Fractiones naturam habent Relationum. Et eatenus aliquo modo Entia appellari possunt. Fractio unitatis non minus est unum Ens, quam ipsa unitas. Nec putandum est, unitatem formalem esse aggregatum fractionum, cum simplex sit ejus notio, conveniens divisibilibus et indivisibilibus, et indivisibilium nulla sit fractio. Etsi materialis unitas seu in actu exercito (sed in genere sumta) apud Arithmeticos ex duabus medietatibus, cum subjectum earum capax est, componatur, ut sit ½ +1/2 = 1 , seu ita verbi gratia, ut valor grossi sit aggregatum valoris duorum semigrossorum. Caeterum ego de substantiis loquebar. Animalis igitur fractio seu dimidium animal non est unum per se Ens, quia non nisi de animalis corpore intelligi potest, quod unum per se Ens non est, sed aggregatum, unitatemque Arithmeticam habet, Metaphysicam non habet. Ut autem ipsa materia, si Entelechia adaequata absit, non facit unum Ens, ita nec ejus pars. Nec video, quid impediat, multa actu subjici uni Entelechiae; Imo hoc ipsum necesse est. Materia (nempe secunda) aut pars materiae existit ut grex aut domus, seu ut Ens per aggregationem.

Infinitum actu in magnitudine non aeque ostendi potest ac in multitudine.

Argumenta contra infinitum actu supponunt: hoc admisso dari Numerum infinitum, item infinita omnia esse aequalia. Sed sciendum, revera aggregatum infinitum neque esse unum totum aut magnitudine praeditum, neque numero constare. Accurateque loquendo loco numeri infiniti dicendum est plura adesse, quam numero ullo exprimi possint; aut loco lineae Rectae infinitae, productam esse rectam ultra quamvis magnitudinem, quae assignari potest, ita, ut semper major et major recta adsit. De essentia numeri, lineae et cujuscunque Totius est, esse terminatum. Hinc etsi magnitudine infinitus esset mundus, unum totum non esset, nec cum quibusdam veteribus fingi posset Deus velut anima mundi, non solum, quia causa mundi est, sed etiam quia mundus talis unum corpus non foret, nec pro animali haberi posset, neque adeo nisi verbalem haberet unitatem. Est igitur loquendi compendium, cum unum dicimus, ubi plura sunt quam uno toto assignabili comprehendi possunt, et magnitudinis instar efferimus, quod proprietates ejus non habet. Quemadmodum enim de Numero infinito dici nequit, par sit an impar; ita nec de recta infinita, utrum datae rectae sit commensurabilis an secus; ut adeo impropriae tantum hae de infinito velut una magnitudine sint locutiones, in aliqua analogia fundatae, sed quae si accuratius examines, subsistere non possunt. Solum absolutum et indivisibile infinitum veram unitatem habet, nempe Deus. Atque haec sufficere puto ad satisfaciendum omnibus argumentis contra infinitum actu, quae etiam ad infinitum potentiale suo modo adhiberi debent. Neque enim negari potest, omnium numerorum possibilium naturas revera dari, saltem in divina mente, adeoque numerorum multitudinem esse infinitam.

Ego philosophice loquendo non magis statuo magnitudines infinite parvas quam infinite magnas, seu non magis infinitesimas quam infinituplas. Utrasque enim per modum loquendi compendiosum pro mentis fictionibus habeo, ad calculum aptis, quales etiam sunt radices imaginariae in Algebra. Interim demonstravi, magnum has expressiones usum habere ad compendium cogitandi adeoque ad inventionem; et in errorem ducere non posse, cum pro infinite parvo substituere sufficiat tam parvum quam quis volet, ut error sit minor dato, unde consequitur errorem dari non posse. R. P. Gouye, qui objecit, non satis videtur mea percepisse.

Caeterum ut ab ideis Geometriae, ad realia Physicae transeam; statuo materiam actu fractam esse in partes quavis data minores, seu nullam esse partem, quae non actu in alias sit subdivisa diversos motus exercentes. Id postulat natura materiae et motus, et tota rerum compages, per physicas, mathematicas et metaphysicas rationes.

Cum dico, nullam partem materiae esse, quae non monades contineat, exemplo rem illustro corporis humani vel alterius animalis, cujus quaevis partes solidae fluidaeque rursus in se continent alia animalia et vegetabilia. Et hoc puto iterum dici debere de parte quavis horum viventium et sic in infinitum. Nullam Entelechiam puto affixam esse certae parti materiae (nempe secundae) aut quod eodem redit, certis aliis Entelechiis partialibus. Nam materia instar fluminis mutatur, manente Entelechia, dum machina subsistit. Machina habet Entelechiam sibi adaequatam, et haec machina alias continet machinas primariae quidem Entelechiae inadaequatas, sed propriis tamen sibi adaequatis praeditas et a priore totali separabiles. Sane et

Schola formas partiales admittit. Itaque eadem materia substat pluribus formis, sed diverso modo pro ratione adaequationis. Secus est si intelligas materiam primam seu τὸ δυναμικόν πρωτον παθητικόν ὑποκείμενον, id est potentiam primitivam passivam seu principium resistentiae, quod non in extensione, sed extensionis exigentia consistit, entelechiamque seu potentiam activam primitivam complet, ut perfecta substantia seu Monas prodeat, in qua modificationes virtute continentur. Talem materiam, id est, passionis principium perstare suaeque Entelechiae adhaerere intelligimus; atque ita ex pluribus monadibus resultare materiam secundam, cum viribus derivatis, actionibus, passionibus; quae non sunt nisi entia per aggregationem, adeoque semimentalia, ut iris aliaque phaenomena bene fundata. Caeterum vides, hinc non putandum, Entelechiae cuivis assignandam portionem materiae infinite parvam (qualis nec datur) etsi in tales conclusiones soleamus ruere per saltum. Comparatione utar: finge circulum, et in hoc describe tres alios maximos quos potes Circulos

inter se aequales, et in quovis novo circulo, et inter Circulos interstitio, rursus tres maximos aequales Circulos, quos potes, et sic finge in infinitum esse processum; non ideo sequetur dari circulum infinite parvum, aut dari centrum, quod circulum habeat proprium, cui (contra hypothesin) nullus alius inscribatur.

Quod statuo non interire Animam animalque, rursus comparatione explicabo. et quae ipsi animae maxime convenit. Et uti natura liquidi in alio fluido affectat rotunditatem, ita natura materiae a sapientissimo auctore constructae semper affectat ordinem seu organizationem. Hinc neque animae neque animalia destrui possunt; etsi possint diminui atque obvolvi, ut vita

eorum nobis non appareat. Nec dubium est ut in nascendo ita et in denascendo naturam certas leges servare, nihil enim divinorum operum est ordinis expers. Praeterea qui considerat sententiam de conservatione animalis, considerare etiam debet, quod docui, infinita esse organa in animalis corpore, alia aliis involuta, et hinc machinam animalem et in genere machinam naturae non prorsus destructibilem esse.

Cum dixi omnem potentiam esse active motricem, intellexi haud dubie potentiam activam, et indicare volui, semper actionem aliquam actu sequi ex potentia conatum involvente, etsi contrariis aliarum potentiarum conatibus refractam.

Causae secundae agent, si nullum sit impedimentum positivum; imo, etsi adsit ut dixi, quamvis tunc minus agant.

Ais substantiam unam, si sola poneretur, habituram infinitas actiones simul, quia nil impediat. Respondeo etiam nunc, ubi impeditur, eam infinitas actiones simul exercere: nam ut jam dixi, nullum impedimentum actionem prorsus tollit. Nec mirum est, quod substantia quaevis infinitas exercet actiones ope partium infinitarum diversos motus exercentium; cum quaevis substantia totum quodammodo repraesentet universum, prout ad ipsam refertur; et quaevis pars materiae a quavis alia aliquid patiatur. Sed non putandum est, ideo, quia infinitas exercet actiones, quamlibet actionem, et quamlibet aeque exercere, cum unaquaeque substantia determinatae sit naturae. Unam autem substantiam solam existere ex iis est, quae non conveniunt divinae sapientiae; adeoque non fient, etsi fieri possint.

Paragraphi postremae, cujus initium est: Sola anima in homine libera est etc, non satis scopum percipio. Quod anima non volvendo, id est qua spiritualis seu libera est, sed ut Entelechia corporis primitiva, adeoque non nisi secundum Leges Mechanicas influat in actiones corporis, jam monui literis praecedentibus. In Schedis autem Gallicis de Systemate Harmoniae praestabilitae agentibus, Animam tantum ut substantiam, non ut simulcorporis Entelechiam consideravi, quia hoc ad rem, quam tunc agebam, ad explicandum nimirum consensum inter corpus et Mentem non pertinebat Finge animal se habere ut guttam olei, et animam ut punctum aliquod in gutta. Si jam divellatur gutta in partes, cum quaevis pars rursus in guttam globosam abeat, punctum illud existet in aliqua guttarum novarum. Eodem modo animal permanebit in ea parte, in qua anima manet, neque aliud a Cartesianis desiderabatur. Praeterea ad actiones mechanica lege exercitas non Entelechia tantum adaequata corporis organici, sed

omnes etiam concurrunt Entelechiae partiales. Nam vires derivativae cum

suis actionibus sunt modificationes primitivarum, quod in Latinis meis

cum Sturmio collationibus explicatum est, alterumque alteri conjungi debet.

Intelligis, plerisque objectionibus facile satisfieri, si ad leges formae revocentur. Rem ipsam autem tum maxime patere arbitror, cum in Breviario totius doctrinae conspectus aliquis ob oculos ponitur, qui haberi potest, licet nondum omnes difficultates ad vivum resectae habeantur, cum potius illa ipsa collatione maxime tollantur. Ut taceam vulgo salvis multis difficultatibus systemata stare. Tali ergo operae manus admoliri fructuosissimum putem, et tum appariturum, quid adhuc potissimum desideratur. Ptolemaeum nostrum sibi gratulari puto, quod honor ei sine onere obtigit, nam publice dignus habitus est qui eligeretur. Opus ejus quod mutuo dederas, pro quo multas gratias ago, prout jussum erat misi Ro. Patri

vestri Ordinis, qui hic vestra sacra obit. Quod superest vale et fave. Dabam Hanoverae 11 Martii 1706.

Deditissimus

Godefridus Guilielmus Leibnitius

P.S. Cum tempestas in melius mutata videatur, hodie Brunsvigam mox rediturus sum. 17 Martii 1706. Literas rectius accipio si vecturae ordinariae Hanoveranae, quam si Magistro Postarum Caesareo committantur. Vectura ter minimum per septimanam

commeat ultro citroque.

TRANSLATION

Leibniz to Des Bosses, Hannover 11-17 March 1706

[Hanover, 11 March 1706]

Most Reverend Father,

Given the present conditions, I have delayed my trip somewhat for the sake of my health. Since your doubts touch on very serious and difficult issues, you will be content if I furnish not what the gravity of the subject requires and your acuteness demands, but what my powers will bear.

Being and one are convertible, but just as there is being by aggregation, so also there is one by aggregation, although this entity and unity are semimental.

Numbers, unities, and fractions have the nature of relations. And to that extent they can in some way be called “beings.” A fraction of a unity is no less one being than the unity itself. And it should not be thought that a formal unity is an aggregate of fractions, for its notion is simple, applicable to both divisibles and indivisibles, and there is no such thing as a fraction of indivisibles. Yet a material unity, that is, one actually effected (but considered in general), is, according to mathematicians, composed of two halves when their subject is able to contain them, just as ½ + ½ = 1, or, for example, the value of a groschen is an aggregate of the values of two halfgroschen. However, I was speaking of substances. A fraction of an animal, or a half-animal, therefore, is not one being per se, since this can be understood only of the body of the animal, which is not one being per se but an aggregate, and has an arithmetical unity and not a metaphysical unity. But just as matter itself, if it lacks an adequate entelechy, does not make one being, so neither does a part of it. Nor do I see what would prevent many things from actually being subject to one entelechy; on the contrary, this is necessarily so. Matter (that is, secondary matter), or a part of matter, exists in the same manner as a herd or a house, that is, as a being by aggregation.

An actual infinity cannot be demonstrated in magnitude as it can in a multitude.

Arguments against an actual infinity assume that, with this allowed, there exists an infinite number; likewise, that all infinities are equal. But it must be recognized that an infinite aggregate is in fact not one whole, or endowed with magnitude, and that it cannot be enumerated. And, accurately speaking, in place of “infinite number,” we should say that more things are present than can be expressed by any number; or, in place of “infinite straight line,” that a line is extended beyond any specifiable magnitude, so that there always remains a longer and longer line. It is of the essence of number, of line, and of any whole whatsoever to be bounded. Consequently, even if the world were infinite in magnitude, it would not be one whole, nor could God be imagined to be the soul of the world, as certain ancient authors hold, not only because he is the cause of the world, but also because such a world would not be one body, nor could it be regarded as an animal, and so it would have only a verbal unity. It is therefore a form of shorthand when we say “one” where there are more things than can be comprehended in one specifiable whole, and when we describe as a magnitude something that does not have its properties. For just as it cannot be said of an infinite number whether it is even or odd, so it cannot be said of an infinite line whether it is commensurable or incommensurable with a given line; and so these are simply improper ways of speaking of infinity, as though of one magnitude, which are based on some analogy, but which cannot be upheld when examined more carefully.

Only absolute and indivisible infinity has a true unity, namely, God. And this, I think, is enough to satisfy all the arguments against an actual infinity, which also ought to apply to a potential infinity in its own way. For it cannot be denied that in reality there are natures of all possible numbers, at least in the divine mind, and thus that the multitude of numbers is infinite.

Speaking philosophically, I no more support infinitely small magnitudes than infinitely large ones, or no more infinitesimals than infinituples. For I consider both to be fictions of the mind, due to abbreviated ways of speaking, which are suitable for calculation, in the way that imaginary roots in algebra are. Moreover, I have demonstrated that these expressions have a great usefulness for shortening thinking, and thus for discovery, and that they cannot lead to error, since it would suffice to substitute for the infinitely small as small a magnitude as one wishes, so that the error would be less than any given; whence it follows that there can be no error. The Reverend Father Gouye, who objects, does not seem to have sufficiently understood my meaning.

To pass now from the ideas of geometry to the realities of physics, I hold that matter is actually fragmented into parts smaller than any given, or that there is no part of matter that is not actually subdivided into others exercising different motions. This is demanded by the nature of matter and motion and by the structure of the universe, for physical, mathematical, and metaphysical reasons.

When I say there is no part of matter that does not contain monads, I illustrate this with the example of the human body or that of some other animal, any of whose solid and fluid parts contain in themselves in turn other animals and plants. And this, I think, must be said again of any part of these living things, and so on to infinity.

I believe that no entelechy is fixed to a specific part of matter (that is, secondary matter) or, what comes to the same thing, to certain other partial entelechies. For matter changes like a river, with the entelechy remaining as long as the machine persists. The machine has an entelechy adequate to it, and this machine contains other machines obviously inadequate to the primary entelechy, but nevertheless endowed with their own entelechies adequate to them, and separable from the prior whole. The

schools of course also admit partial forms. And so the same matter subsists in many forms, but differently, as a function of its adequation. It is otherwise if you mean primary matter or primary passive power, primary substratum, that is, primitive passive power or the principle of resistance, which consists not in extension but in a prerequisite of extension, and completes the entelechy or primitive active power, with the result that it produces a complete substance or monad, in which modifications are contained virtually. We understand such matter, that is, the principle of passion, to endure and to adhere to its entelechy; and in this way from many monads there results secondary matter, together with derivative forces, actions, and passions, which are only beings through aggregation, and thus semi-mental things, like the rainbow and other well-founded phenomena. Yet you see that it should not be concluded from this that an infinitely small portion of matter (such as does not exist) must be assigned to any entelechy, even if we usually rush to such conclusions by a leap. I shall use an analogy. Imagine a circle; in it draw three other circles that are the same size and as large as possible, and in any new circle and in the space between circles again draw the three largest circles of the same size that are possible. Imagine proceeding to infinity in this way: it does not follow that there is an infinitely small circle or that there is a center having its own circle in which (contrary to the hypothesis) no other is inscribed.

As to my claim that the soul and the animal do not perish, I shall again explain it with an analogy. Imagine an animal as a drop of oil and the soul as some point in the drop. If the drop is now divided into parts, the point will exist in one of the new drops, since any part in turn is transformed into a spherical drop. In the same way, the animal will survive in that part in which the soul remains and which best agrees with the soul itself. And just as the nature of the liquid in any fluid aims at sphericity, so the nature of the matter constructed by the wisest author always aims at order or organization. From this it follows that neither souls nor animals can be destroyed, although they can be diminished and concealed, so that their life does not appear to us. And there is no doubt that in generation, as also in corruption, nature obeys certain laws, for nothing of divine workmanship is lacking in order. Moreover, whoever reflects on the doctrine of the conservation of animals must also consider, as I have shown, that there are infinite organs in the body of an animal, some enfolded in others; and from this it follows that an animated machine, and in general a machine of nature, is not absolutely destructible.

When I said that every power is actively motive, I certainly meant active power, and I wanted to indicate that some actual action always follows from a power involving endeavor, although it is checked by the contrary endeavors of other powers.

Secondary causes act if there is no positive impediment; indeed they will act, as I have said, even if it is present, although they then act less.

You say that one substance, if we should suppose one alone, would have infinite actions at the same time, since nothing impedes it. I reply that even when it is impeded, it exerts infinite actions at the same time; for, as I have already said, no impediment destroys an action completely. And it is not surprising that any substance exerts infinite actions with the help of infinite parts exercising different motions, for any substance represents the whole universe in some way, according to how it is related to it, and any part of matter is affected in some way by every other. But it should not be thought on this account that, since it exerts infinite actions, it exerts every action whatsoever and every action equally, for each and every substance is of a determinate nature. However, that there should exist one substance alone from among these is something that does not agree with divine wisdom; thus it does not happen, although it could happen.

In the last paragraph, which begins, “The soul alone is free in man,” I do not really see the problem. I indicated already in my previous letter that the soul does not influence the actions of the body by deliberating, that is, as something that is spiritual or free, but rather as the primitive entelechy of the body, and thus only according to mechanical laws. In my French essays discussing the system of preestablished harmony, on the other hand, I considered the soul only as a substance, and not at the same time as the entelechy of the body, since this did not pertain to the matter I was then concerned with, the explanation of the unquestioned agreement between the body and the mind; nor was anything else expected by Cartesians. Besides, in actions exerted according to mechanical laws, not only the entelechy adequate to the organic body, but also all partial entelechies, come

together. For derivative forces, together with their actions, are modifications of primitive forces, as I explain in my Latin exchange with Sturm; the one must be joined with the other.

You will gather that many objections are easily answered if they are subjected to a formal analysis. But I think the subject is made most clear when an overview of the whole doctrine is placed before the eyes in a summary, which can be done even if all difficulties have not yet been fully addressed, since they are greatly reduced through the comparison itself. Although

I would not say so publicly, despite many difficulties the system stands. I therefore think it would be most profitable for a work of this sort to be undertaken, so that there might then appear what until now has been most urgently required.

I suspect our Tolomei is pleased that honor came to him without obligation, for he was universally judged worthy of being elected. As ordered, I sent his work, which you had exchanged with me, for which I am very grateful, to the Reverend Father of your order who is visiting your holy mission here. For the rest, farewell and think kindly of me. From Hanover,11 March 1706.

Most faithfully,

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

P.S. Since the stormy weather seems to have changed for the better today, I shall soon be setting out again for Brunswick. 17 March 1706. I receive your letters more consistently if you entrust them to the regular Hanover coach rather than to the imperial postmaster. A coach comes and goes at least three times a week.

⇐ BACK

-

Dr. Osvaldo Ottaviani

Translation